Terence Gower

The Workshop Pavilion (Pabellón de talleres) is a free-standing, double-height structure designed to fit snuggly into the monumental sculpture gallery of MUSAC in Léon, Spain. The work is hyper-functionalist, designed to flexibly serve the needs of the museum’s education department, while recycling material left over from past museum exhibitions.

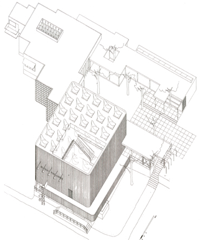

The main volume of the pavilion is a lightweight, low cube standing on narrow pilotis and suspended over a 6 x 7 metre carpeted area. The carpet delineates an intimate, human-scaled zone of activity, with a ceiling height of 270 cm. Faced in banners from past shows, this sheltering structure functions like a marquee of the museum’s history.

The active, changing functions of the museum’s education department (DEAC), are served by mobile units, plugged into this larger structure, like satellites docked around a mothership. These mobile units—an arts and crafts unit, a video/computer unit, and a radio/audio unit—are support platforms for the numerous activities of DEAC. They can be deployed in place around the mothership structure, or wheeled out into the museum and beyond. With these units DEAC can easily install its workshop apparatus—equipment, chairs, tables, etc.—in any context, whether a specific museum exhibition, the high-traffic museum lobby or bar, or out to the surrounding plaza, sidewalks or playground.

The Workshop Pavilion is one in a series of my works that use the pavilion typology to analyze the complicated relationship between display and function in architecture. The foundation of my project is a study of five mid-twentieth century exhibition pavilions: Alvar Aalto’s 1937 Finnish Pavilion, Gerrit Rietveld’s 1953 Sonsbeek Pavilion, Mies vand der Rohe’s 1929 German Pavilion at Barcelona, Jose Luis Sert’s 1937 Spanish Republic Pavilion, and Oscar Niemeyer’s 1939 Brazil Pavilion. This study, titled 5 Notable Pavillions, is documented in detail in my book Display Architecture. Each of these five pavilions was central to their architects’ oeuvre and thus influenced the development of modern architecture. Yet, unlike a factory or hospital, an exhibition pavilion has a very light functional program—it is basically a box designed to display artifacts and to display itself at the same time. This functionality issue of the pavilion problematizes the modern architect’s theory of function as a determinant of architectural form.

Alvar Aalto designed a series of elegant wood-clad boxes to showcase the timber trades of Finland for the 1937 Paris World Fair. Though he used a barebones functionalist design system, he used the subject of his display, wood, in the structure and cladding of the Finnish pavilion. He did not clad the pavilion in fine wood paneling, but used standard construction-grade lumber. The material and structure came together to create a pavilion of great beauty. One could say that Aalto managed to aestheticize function in his pavilion.

My pavilion projects continue to test this complicated relationship between function, beauty and display. Each of my pavilion designs takes one of the 5 Notable Pavilions as a formal starting point and then brings in a function: My Workshop Pavilion uses Aalto’s Finnish Pavilion as a model, then introduces the function of the workshop. Though each of my pavilions is designed for a specific utilitarian role, their functionality is questioned further by their status as art objects. Their resulting ambivalent position in the art museum or collection is a neat allegory for the perpetual renegotiation of the function and role of art in society.