Excerpt from Display Architecture

Navado Press, Berlin/Trieste, 2007

BICYCLE PAVILION

Commissioned in 2002 by the Colección Jumex in Mexico City and installed on the grounds of the Jumex factory, the pavilion measures 18.05 metres long by 4.8 metres high by 1.8 metres wide. It is made of enameled steel and vinyl-coated glass panels. The pavilion is attached to the fence separating the employee and visitor parking lot from the factory’s shipping area. Commissioned by: Patricia Martín, La Colección Jumex. Producer: Héctor Zamora. Fabricator: SPC: Servicios Profesionales de la Construcción, SA de CV

Social Economics

I came of age in Canada, where media artists were Marxists who dismissed the term “artist” as too bourgeois (they opted instead for the term “cultural producer”). The term has an anti-aesthetic quality to it that still appeals to my Functionalist side. When Jumex commissioned a large installation, the “cultural producer” in me saw an opportunity: the Jumex gallery is inside the Jumex factory, and the commission seemed like a unique opportunity to interact with real factory workers.

When I received the invitation to do a project from the Jumex Collection’s founding director, Patricia Martín, my first idea was to create a beautiful flow-chart detailing the levels of production and distribution in the juice factory. This chart, I thought, would be permanently installed on the interior wall of the building housing the shipping department. It would even feature a schematic of the factory hierarchy. Unfortunately we were forced to scrap that idea because of security concerns and anxieties about industrial espionage.

I then became interested in how the workers lived outside the factory buildings. I immediately noticed a crude, tin-roofed bicycle shack in one of the parking lots. The site appeared to be a natural interface between the factory and the collection, between art and utility, display and function. I decided to work with this site, creating a structure that would highlight its tensions and contradictions.

As an interface, the structure would have two functions, one associated with the worker, and the other with the art viewer. The pavilion’s lower level constitutes the reinstated bicycle storage shed, while the upper level is a belvedere, a “mirador” or promenade from which to gaze over the factory grounds. The promenade deck is designed to frame certain vistas and to put the exquisitely maintained factory grounds on display in an experience similar to art viewing. These two pavilions, though joined in a single structure are also separated by the barrier of the metal deck. But transgressions of this barrier have been very welcome:

At the work’s inaugural reception, one guest (fellow Canadian artist Richard Moszka) arrived by bicycle from Downtown Mexico City. He stored his bicycle in the pavilion alongside those of afternoon- and evening-shift workers. Jumex Collection openings are famous for often running more than twelve hours.

The Jumex Corporation offers workshops on contemporary art to its workers, their families and local schoolchildren. This is the moment when a storage shed becomes sculpture and the worker gets a new view of the familiar grounds of the factory.

Models

My design for the Bicycle Pavilion is based on two models; Josep Lluis Sert and Luis Lacasa’s Spanish Republic Pavilion at the 1937 Paris International Exhibition and the Mexico City Polytechnic designed by Reynaldo Pérez Rayón and completed in 1964.

The Mexico City Polytechnic (IPN, Zacatenco Campus) is located near the Ecatepec exit of Mexico City, and is one of the clearest examples of Mexican Functionalism. Yet Pérez Rayón’s design is full of contradictions. The IPN campus was started in the late 1950s and clearly looked to Mies van der Rohe’s recently completed Illinois Institute of Technology as a model. The architect was aiming for the same clear expression of steel building technology, yet by 1959 that technology hadn’t fully arrived in Mexico. The building trade hadn’t been mechanized as it had in the US. Paradoxically, handcrafted steel masterpieces like the IPN were erected to symbolize the ideals of modernity and technology that had not yet reached the country. The IPN, in other words, looked more modern than it actually was: it gave the appearance of being built out of mass-produced elements when it fact it was erected using handcrafted materials.

The IPN (see image below) was built at an impressive scale. The row of classroom buildings seems to recede into the distance, representing the orderly education of the populace of a vast, well-ordered future society. I am fascinated with the pilotis in this composition. They raise the building off the ground and make one think of how the legs of a vitrine support the glass box. They are display cases for Modernism, technology, and the bright future of Mexico.

The Bicycle Pavilion also stands on square steel pilotis and is so well handcrafted and polished by its builders that it gives the impression it could have been produced on an assembly line. In fact, it was assembled about a hundred metres from its present site then carried and bolted into place. We were not allowed to weld on site because of the presence of a large gas tank.

Mexico City Polytechnic (Instituto politécnico nacional). Reynaldo Pérez Rayón, 1964

The pavilion design is also based on certain characteristics of the Jumex factory environment. Its metal elements are painted the same grey as the factory ironwork; the façade module is based on the measurements of the adjoining fence. And finally, the structure plays on the form of the huge trailer trucks that pass every few minutes, en route to the factory distribution centre.

Colour

I chose the colors for the Bicycle Pavilion for their Modernist feel. The warm red of the interior panels is the red of the early Modernist avant-gardes, of de Stijl, Constructivism, Purism, the Bauhaus. Though the ideologies and mandates of these groups varied widely, they were united in a call for a rupture with an antiquated past. I believe this colour is embedded with traces of that call for change.

Function

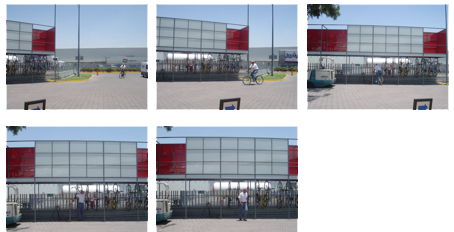

The Bicycle Pavilion is the site of a daily pilgrimage by factory workers arriving by bicycle from the surrounding neighbourhoods of Ecatepec. The images below show an interaction with the pavilion.

Jumex factory worker arriving by bicycle. Photography: Luz

The drawings titled Spec. Pavilions (shown on the following pages) present a series of imaginary, functional reassignments for the Bicycle Pavilion. In each, the panel composition of the upper level changes slightly to match the rearrangement at ground level. All of these new assignments internalize the “function” of the upper observation deck, since each pavilion revolves around the gaze and its multiple functions: art-viewing, cruising or surveillance. Spec. Pavilions features the following structures:

1. Gallery Pavilion (to be installed either outdoors or in a large indoor space). The lower level functions as an art gallery reception desk, library, storage, and director’s office. The upper level affords views of the surrounding artworks.

2. Cruising Pavilion. The lower level is modeled on a traditional European pissoir, a traditional site for gay cruising. An ice-cream stand has been added as a discreet homage to La Copelia, Havana’s tropical-modern gay cruising mecca and ice-cream parlor. The upper level is provided for sighting “fresh meat” and police cars. All illegal activity is encouraged.

3. Surveillance Pavilion. The lower level provides an enclosed cabin for the surveillance crew. A bank of monitors comes with a closed-circuit connection to oscillating exterior cameras. The upper deck may be used as an observation platform or gun turret.