Notes on Display Modern (Hepworth)

Terence Gower

MODERN ART

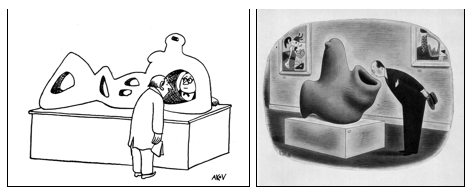

I became interested in Barbara Hepworth when I was contemplating sculptors who could be said to “represent” an idea of modern art. My search started off in analyzing popular period impressions of modern sculpture. My primary tool was the period cartoon. From the late 1940s through the 1960s magazines like the New Yorker published a number of cartoons about modern art and by looking closely at the depictions of the artworks one can form an idea of what modern art looked like in the popular imagination of the period.

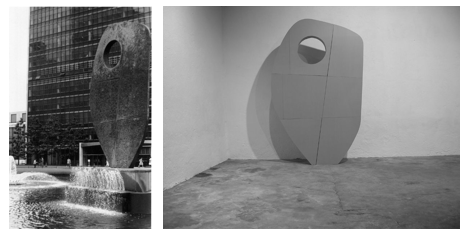

I used these depictions to identifying the quintessential modern artist—the artist whose work signifies the modern. Because we are dealing with the mutable and ephemeral world of the (popular) imagination, I decided to eliminate artists whose “styles” were too heavily identified with their names: Henry Moore or Isamu Noguchi are good examples of this problem. I wanted the work to be as abstract as possible to keep the imagery floating in the untethered world of imagination. The work should be as reduced as possible, as complex forms are too difficult to assemble into a clear mental image. Lastly, the artist’s work should be on public display around the world. Barbara Hepworth was an obvious choice. She was an artist who experimented with many forms in search of the perfect balance of proportions. Single Form is her formally most reduced work, yet it is also the largest at 6.4 metres high. It is also at the centre of the world stage, installed in the forecourt of the United Nations building in New York. The work floats there, almost invisible in its simplicity, yet might just appear to us if we close our eyes and think of the words “modern sculpture”.

In Display Modern II, Hepworth’s Single Element is recreated at half scale in cardboard. The 12-photograph series reads like a photo-conceptual process piece.

THE STUDIO

Hepworth was often photographed in her studio surrounded by her work. Her sculptures are shown in various states of production, displayed on carving stands as well as on museum plinths. There is no doubt that Hepworth surrounded herself with her own work as part of her working method—to uncover themes and connections between completed works and to determine next steps.

But there is also a sense that the works (and perhaps the figure of the artist) were consciously “set up” for the photograph. In other words, the work seems to be carefully put on display for the lens of the camera. Brancusi is well-known for his studio displays, in which the meaning of the works is carefully constructed through their interrelationships as captured by the camera or by the visitor to the studio. Hepworth visited Brancusi’s studio in Paris and perhaps came away with some of his spirit of display. Display Modern I is made up of 1:1 scale reproductions of Hepworth’s sculptures, recreated in papier mâché. The sculptures are grouped simply, to evoke Hepworth’s studio displays.

MATERIAL

I use cardboard and papier mâché to create scale copies of Barbara Hepworth’s sculptures. This is a technique commonly used to quickly and inexpensively generate volume for store displays and theatre sets. The simple materials in evidence in the sculptures—cardboard and craft paper—give these pieces the air of a stand-in or model for the real sculptures, which are made of stone, bronze or wood. The cardboard and papier maché technique is additive, like architecture, where the final form is arrived at through a process of building up volume. Hepworth’s originals, by contrast, are created through a subtractive process of carving away at a block of stone or wood.

The materials used in this work also test the relationship between the physical and psychological weight of sculpture. My sculptures fill the exact same volume of space as Hepworth’s originals. But if we were to set them side by side, could we detect a different gravity from the stone or wood original and the paper copy?